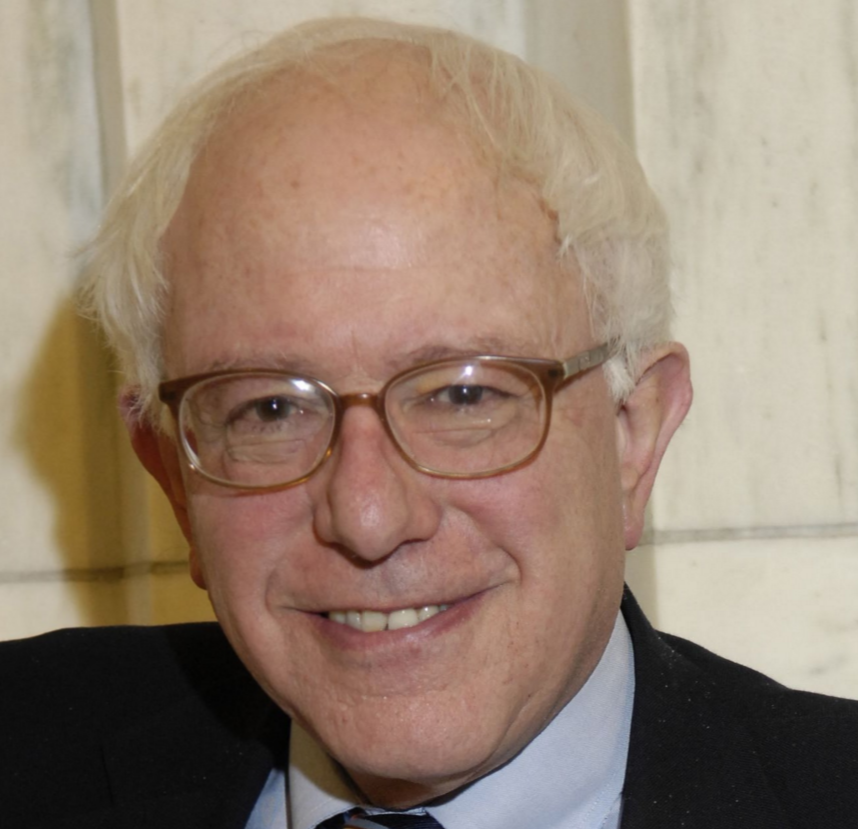

PBHFA’s Director Dr. Anna Pomeranet’s research on financial transaction taxes was featured in a Wall Street Journal article focused on Bernie Sander’s tax plan.

What would Bernie Sanders’ Wall St. tax look like?

By John Carney

Published: Feb 14, 2016 6:36 p.m. ET

Bernie Sanders wants to raise a lot of money from Wall Street.

Mr. Sanders’s plan isn’t to ask Wall Street for money. It’s to demand it in the form of a financial-transaction tax.

Proponents claim the tax would collect tens of billions of dollars, discourage speculative and high-frequency trading, and make markets safer and less volatile. Its opponents say the revenue estimates are overstated and the tax will actually make markets more volatile.

Mr. Sanders wants to use funds raised by this tax to pay for his college-education agenda, which includes making public colleges free, cutting interest rates on student loans and increasing financial aid. The costs of these proposals–$75 billion per year by Mr. Sanders’s count–could be fully paid by the tax, according to Mr. Sanders.

Under a bill Mr. Sanders introduced last May, investors would be required to pay an excise tax on any transfer of a stock, bond, partnership interest or derivative. Stock trades would incur a 0.5% tax rate, or $5 for every $1000 of stocks traded. Bond trading gets a 0.10% tax rate. Derivatives a 0.005% tax rate.

Although those tax rates seem quite small, in theory they could raise quite a lot of revenue for the government because of the size of U.S. financial markets. The total dollar value of U.S. stocks is around $25 trillion and more than $300 billion in shares is traded on a typical day. The bond market is even bigger, with nearly $730 billion trading on an average day last year.

The idea of taxing financial transactions didn’t originate with Mr. Sanders. It is often called a “Robin Hood Tax” or a “TobinTax,” after Nobel laureate James Tobin, who proposed a tax on currency trading back in the 1970s. Unlike Mr. Sanders’s proposal, Mr. Tobin’s tax wasn’t primarily aimed at raising revenue. Rather, the point was to discourage speculation that Mr. Tobin said was destabilizing foreign-exchange markets.

Similar taxes have been advocated by many prominent economists over the years, including John Maynard Keynes, Joseph Stiglitz and Lawrence Summers. At least 40 countries currently or previously have had financial-transaction taxes of one sort or another.

The U.S. imposed a small tax on stock transactions beginning in 1914, to help raise funds to fight World War I. Initially the tax was set at 0.02% but later ranged between 0.04% and 0.06% until its repeal in 1966. New York State and New York City jointly had a tax on stock trades until 1981. In fact, New York State still collects a stock transfer tax–and then refunds the money collected to the investors that paid it. So investors are, in effect, giving Albany an interest-free loan.

The New York tax was the subject of a study by Bank of Canada economist Anna Pomeranets and Rutgers University economics professor Daniel Weaver. They found that the tax made stocks more volatile, depressed stock prices, widened bid-ask spreads and made capital more expensive for businesses. For example, when the tax was raised 25% in 1966, bid-ask spreads widened from 1.76% to 2.05%.

The majority of the academic research into transaction taxes has reached similar findings: Taxes either have no effect on volatility or they increase volatility.

Why would markets become more volatile when financial transactions are taxed? When an activity is taxed, people tend to do less of it. So trading volumes decline–sometimes sharply. An IMF study found that trading volume invariably fell when transaction taxes were imposed.

According to the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center, a 0.01% tax would reduce volume by 24% in the first year, with volume falling even further in the future. Much of that reduction would likely come from discouraging high-frequency trading and “unproductive” speculation, according to the Tax Policy Center.

What would a tax do to stock and bond prices? It’s impossible to know for sure, of course. But because investors value liquidity, anything that makes buying or selling more costly tends to push prices down. When Sweden put in place a 1% tax on equity trades in 1983, the result was a 5.3% decline on the Stockholm Stock Exchange.

According to the IMF study, the impact on prices would depend on the average holding period for a particular asset class. So stocks that trade frequently would likely decline the most. Less frequently traded securities, like corporate bonds, would be expected to hold up better.

The economy, too, could suffer. When the European Commission looked at the issue, it found that a tax of 0.1% would reduce gross domestic product by 1.76% in the long run. That’s mainly because the tax raises the cost of capital, resulting in less investment and diminished economic output.

There are also questions about how much revenue the tax would raise. For starters, anything that makes stock prices drop sharply reduces how much the government collects in capital-gains taxes.

When the Joint Committee on Taxation looked at an earlier proposal for a financial-transaction tax, it estimated that around $35 billion a year would be collected. The Tax Policy Center estimates the maximum that could be collected would be $50 billion a year.

Even investors who don’t trade often and primarily own mutual funds would feel the pinch. Because mutual funds must buy and sell securities to adjust their portfolios and obtain cash for investor redemptions, they would often incur the tax. According to the industry-sponsored Investment Company Institute, a transaction tax would potentially increase the expense of investing in an equity index fund by one-third.

On the other hand, if the tax discouraged individual investors from trading too frequently–an all-too-common mistake–it might actually improve their returns over the long run.

The tax promises a smaller, slower market offering lower returns to investors. For some voters, however, that might be the goal.